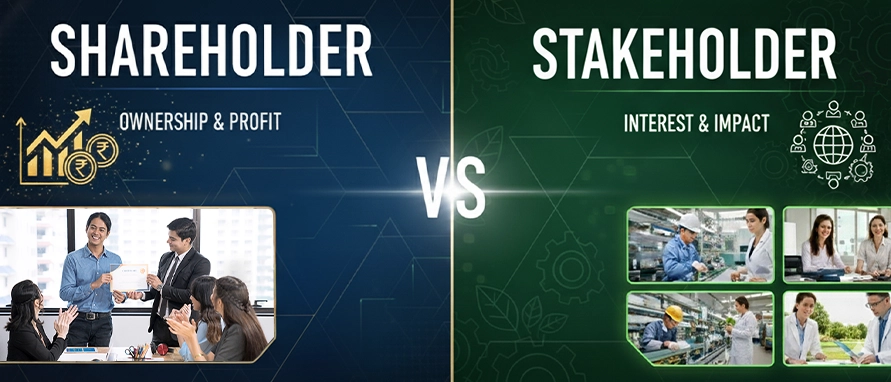

A stakeholder is any individual, group, or organisation that is affected by or has an interest in a company's operations, outcomes, or decisions. Unlike shareholders, stakeholders may or may not own equity in the business. Their concerns often go beyond profit, encompassing ethical practices, social impact, sustainability, and long-term business health.

Stakeholders can be internal (within the company) or external (outside the company), and their needs often influence company strategy, compliance, and reputation management.

Key types of stakeholders include:

Employees – Rely on fair wages, job security, and safe working conditions.

Customers – Expect product quality, service, and value.

Suppliers & Vendors – Depend on consistent contracts and payment terms.

Communities – Are impacted by environmental and social practices.

Governments & Regulators – Monitor legal and tax compliance.

Shareholders – Also considered stakeholders, but with ownership rights.

Stakeholders reflect a company’s broader responsibility to society and business ecosystems.

.jpeg)